On a Wednesday press conference, Michael Ryan at the WHO’s Health Emergency Program caused indignant headlines to ripple across the globe faster than the corona virus can infect your respiratory tract cells. Sweden’s somewhat diverging corona fighting strategy has been treated with outrage, anger, and disbelief in global news coverages – plus a handful of libertarians celebrating its newly-acquired laissez-faire status.

“If we are to reach a new normal,” said Ryan, “Sweden represents a future model.”

That can of worms should have remained closed, reasoned newsrooms across the planet. How dare you celebrate this irresponsible, cruelly capitalist exercise in human sacrifice and their Don’t-Care approach to the biggest global disaster and suffering of our times?

Yes, hysteria and overreaction have been major features of the world’s response to this virus, among politicians, journalists, and everyday people alike.

To recap: the Swedish government, judging its country to be sufficiently different from others and on advice of their surprisingly competent public servants, opted for less restrictive tools in fighting this disease. Sweden did not do nothing. The chief epidemiologist of the Public Health Agency, Anders Tegnell, has repeatedly stressed that Sweden follows the same strategy everyone else does: reduce the transmission of the disease; flatten the curve; expand hospital capacity; protect vulnerable groups.

The difference so far has been that Sweden does so by trusting that its citizens would opt prudently. That is: work from home if you can, which hip companies like Spotify urged their employees to do before the authorities did; avoid gatherings, which meant that a bunch of festivals, concerts, and events cancelled on their own and frequently reimbursed participants; wash your hands and use hand sanitizers, so universally embraced that even my town’s coolest kids – whose classes are naturally not cancelled – do so with fervor; don’t cheek-kiss your friends and family, which no self-respecting and intimacy-shy Nordic person would do anyway.

In other words, these are some of the same social distancing advice that various U.S. governors have forced down Americans’ unwilling throats. In addition to that, Sweden avoided policies that projected political decisiveness but had no scientific rationale behind them, like closing borders and schools.

Life here is completely different, but still remarkably normal. Runners and park visitors keep their advised distance; supermarkets open early for the elderly and put out hand sanitizers for all to use; restaurants separate their tables a bit more – and everything else stays open.

With extremely individualistic inhabitants that trust their public institutions to a remarkable degree, austere epidemiologists merely had to issue guidelines to get a large behavioral effect – strengthened by a media that arranged nuanced Q&As with professors and other specialists reporting statistical reality and prudent advice rather than clickbait-y hysteria and political pie-throwing. Now, Ryan makes it clear that Sweden is far from a laissez-faire paradise in its epidemiological response (or otherwise):

Sweden has not avoided controlling Covid-19; it’s taken a very strong strategic approach to controlling Covid-19 across all of the elements of society. What is has done differently is that it has really, really trusted its own communities to implement that physical distancing.

Deal with your population like they’re adults and they behave accordingly. Ryan particularly stressed the “special relationship” the Scandinavian country has with its citizen, a point I’ve stressed several times on these pages. That’s good news and bad news. The good is that freedom works, as well or perhaps even better than a central commander applying one-rule-fits-all for millions and millions of people. The bad news is that such a model may not easily translate into other nations that have different institutions, norms, and cultural values. As PolitiFact has it: “Sweden goes voluntary, not mandatory”. (Even this has a limit as the authorities a few days ago closed five Stockholm bars after they failed to adhere to public guidelines when maintaining insufficient distance between their customers.)

The crux of the matter has been explained many times, for instance here by Paul Franks, an epidemiologist at Lund University:

Protecting a population from becoming infected with aggressive containment is like protecting a forest in the path of wildfire – unless continuous firefighting efforts are made, the forest will eventually burn.

Did it work?

So far that’s anybody’s guess. Wall Street Journal’s Joseph Sternberg correctly noted that, on this, the jury is still out:

I have no idea whether Sweden’s more modest approach to the Covid-19 pandemic—keeping schools and restaurants open while restricting visits to retirement homes—will be a success or a colossal and deadly mistake. No one else will know either, probably for months.

In time, we’ll have better numbers – more complete infection numbers, fatality rates, and recoveries as well as economic and financial damage done (such as jobs lost, businesses destroyed and value eradicated). Economists and other social scientists will have a field day trying to separate the damage done by the disease from the seemingly outrageous damage done by government officials.

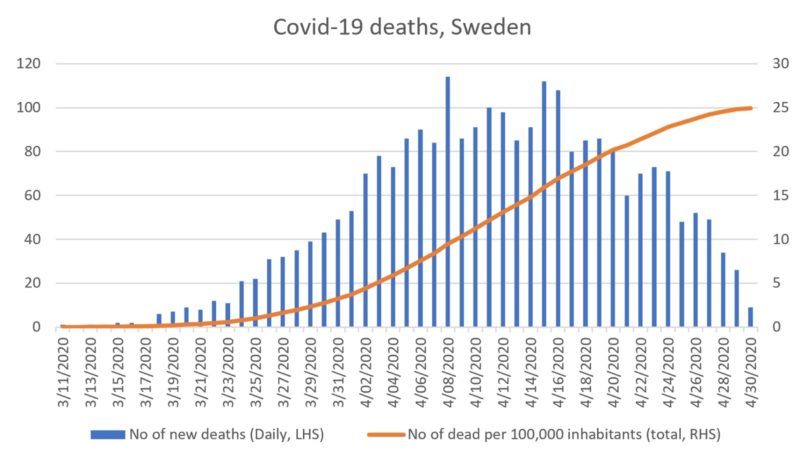

Until then, we have to make do with what we have. The number of new Covid-deaths reported by Sweden’s Public Health Agency peaked in mid-April, suggesting that those dying contracted the disease in late-March; the steady decline in deaths since then point to the effectiveness of measures taken (or perhaps the limits of the virus itself):

Perhaps I’m overly cheerful here, but the per-capita rate looks like the S-shaped (not exponential) curve we expect pandemics to have, and the steadily declining number of new casualties suggests that at least something is working.

Some upset commentators have pointed out that Sweden still has an awfully high death rate, worse than other Nordic countries or Germany and the United States (while not quite as bad as the UK, Italy or Spain). Sweden’s deviant and lenient policy has “contributed to one of the world’s highest COVID-19 death rates, exceeding that of the United States.”

True, using numbers from April 30, Sweden’s per-capita death rate stands at 25 per 100,000 inhabitants while the U.S. number is 18. But the U.S. is vast and most (rural) places have hardly any infections and very few dead. A different picture emerges if we compare only the epicenters of each country: New York City and Stockholm. One reason I want to make that comparison is that both regions account for large parts of their countries’ respective deaths. Covid-19, so far, is predominantly a New York affair, as Bret Stephens aptly argued in the New York Times. Similarly, Stockholm proper (not including two adjacent regions from which there is usually extensive commuting) accounts for over half of all Swedish deaths and more than one-third of all confirmed cases . In the table I also include deaths from Stockholm’s adjacent administrative regions Sörmland and Uppland:

| New York City | Stockholm | |

| Metro area population | 20.1 million | 2.3 million |

| Deaths | 18,076 | 1,665 |

| Per-capita deaths (per 100,000) | 89.9 | 72.4 |

| Share of country’s deaths | 29.6% | 64.4% |

I noted in an earlier piece that the population density of Stockholm roughly equals Chicago or Boston, so some consideration might be given for New York City’s extremity here. Nevertheless, depending on our political priors we can lament or celebrate Sweden’s approach all we want, but laissez-faire Stockholm seems to fare better than locked-down New York – and that’s before discussing any difference in financial shocks, which ought to be much worse in New York.

What’s going on in Sweden is remarkable, which now even the WHO’s epidemiologists admit.

This article is republished with permission from the American Institute for Economic Research.