Tinder is launching a new paid version which will charge for certain add-on features like the ability to “rewind” and select a profile which was accidentally rejected. However, in a controversial move, the company intends to charge people aged 18-27 a monthly price of $9.99, while it will charge those who are older than that a doubled price of $19.99. While one expert called the move “sleazy,” Tinder has insisted that the pricing was based on “extensive” tests. A Tinder spokeswoman compares the strategy to the one employed by Spotify in regards to students.

The raising of prices is often criticized in progressive circles as “unjust.” However, this move by Tinder could create a better project for its consumers: principally young, hormone-filled college students.

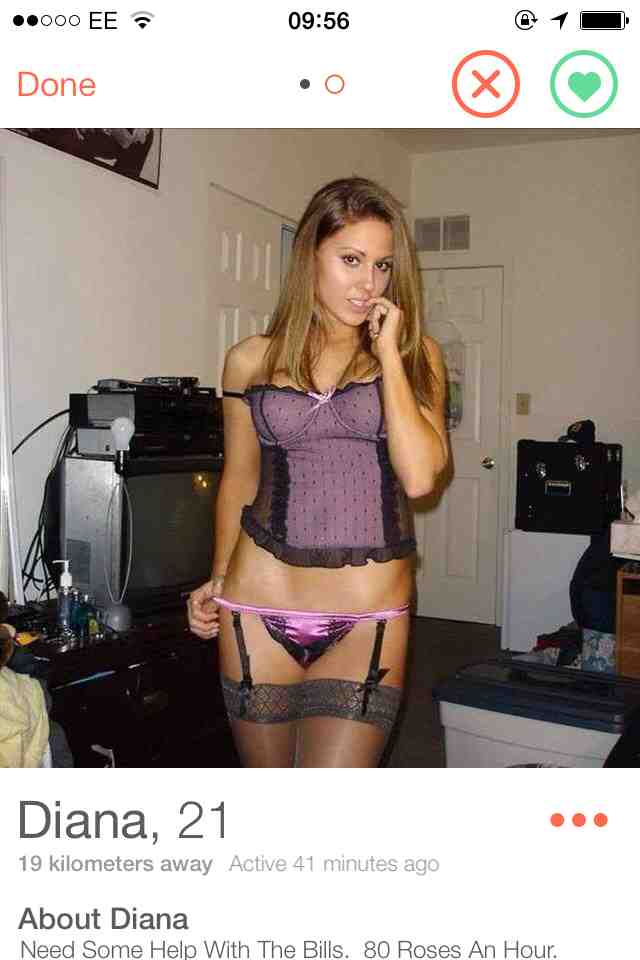

By creating a very simple barrier, the “hook-up” app can ensure quality over quantity. As it is, the app has long been infiltrated by female “profiles” purporting to be owned by regular females, which are actually controlled by either pornographic websites attempting to gain traction or prostitutes who, obviously, are asking a much higher price than most are willing to pay.

19.99 Roses For Full Service

This protection created by Tinder makes it more difficult for these con artists to thrive inside Tinder’s infrastructure. They likely cannot afford to spend money on frivolous expenses, and therefore they will be less keen upon bothering others with fruitless endeavors. Under Tinder’s “premium” app, access to the “best” matches may be precluded if one is not willing to pay. This can act as a gate-keeping authority. Any commercial actor has only limited resources; it cannot allow for time or money to be used where success is difficult to come by.

Tinder’s introduction of a paid version is a perfect example of how markets do not need government regulation; free markets will always surely regulate themselves. If Tinder’s price is deemed by consumers to be too high, it will be forced to change its pricing if it wishes to survive. Conversely, if the pricing is deemed to be an accurate representation of a fair market value, Tinder can use surplus profits to further satisfy its buyers and employees. As millions turn to billions, more money will be put back into the economy to benefit financial markets and society as a whole.

Companies like Tinder also have a responsibility to provide an adequate product and maintain their standing through self-imposed boundaries. Tinder knows better than any government what they must do in order to please their clientele. By providing free and paid versions contemporaneously, they can find out quickly just how important certain features really are to users; if nearly everyone is willing to pay so that they may “rewind” their decision to reject a suitor or so that they may “travel” to another area to search for potential mates, Tinder is able to prime what is important in future updates.

Better yet, if Tinder does not serve its customers well enough, a competitor is bound to appear and overtake them. This is why some praise must be given for taking such a risky step. There have been dozens of dating sites which have appeared over the years, but none have made the impression that Tinder has. The free market requires that services in every field adapt. One doesn’t have to look further than Facebook and Twitter, once-tiny social networking giants which quickly overtook then-behemoth MySpace in less than a decade.

Only time can tell if Tinder’s strategy will work. However, we must give such action the benefit of the doubt and allow it to take its course. Tinder has a lot on the line, but capitalism ensures that no matter what happens, consumers will win.