Published: February 28, 2015

A recent push by Oklahoma conservatives to possibly replace the newly-revised AP United States History (APUSH) exam has produced a great deal of backlash, far greater than one would normally expect in the often-dry debate over how to formulate American education standards.

Salon blasted Oklahoma’s legislators as “demented” for opposing the narrative of the College Board. NPR describes them as upset over the fact that slavery, the suffering of American Indians, and the internment of the Japanese “make the cut” into the new framework. A Washington Post editorial has even tied APUSH critics with the Tennessee lawmakers who banned the teaching of evolution nearly a century ago.

The sentiment, to say the least, is that critics of APUSH simply want history classes to be right-wing patriotic propaganda, devoid of anything negative and promoting a saccharine image of the country’s history.

The truth is, as usual, somewhat more nuanced.

APUSH critics aren’t demanding that American history be whitewashed, or that classes reflect conservative political ideology. In fact, for the most part, they’re just asking for the return of the old APUSH course framework and test, which existed until this year before being displaced by a brand new framework.

That framework, they argued, was more balanced, more rigorous, and less prescriptive in how individual material should be covered.

Jane Robbins, a senior fellow with the American Principles Project and one of the most vocal critics of the new APUSH test, spoke with The Daily Caller News Foundation to clarify the flaws that she sees at the heart of the new exam.

The problem, Robbins says, isn’t that the new APUSH covers slavery, Japanese internment, or any other bad aspects of American history. The previous APUSH exam covered the same things, and raised no major objections. Rather, she said, the core problem is one of overall tone and how subject matter is framed.

That is, American history primarily through the lens of oppressed minorities.

“[The narrative is] there are a couple of bright spots, but generally our history is one long depressing story of identity groups in conflict,” Robbins said. ”Everything shall be looked at through gender, class, race.”

The previous AP framework, which few have complained about, also gave time to identity group issues. Courses were expected to cover 12 themes such as “economic transformations” and “war and diplomacy.” One such theme was “American diversity,” which intended for students to learn about the ”roles of race, class, ethnicity, and gender in the history of the United States.”

In contrast, the new APUSH covers only seven core themes. While one of those themes is explicitly on “identity,” issues of race, gender, and class pop up in the other six as well. This focus, Robbins argues, encourages a narrative of American history that leads to a heavy focus on group conflict and resulting oppression, while de-emphasizing more positive parts of history.

“It’s all forces of history,” she said. “Nothing on what we see as the great things of our history.”

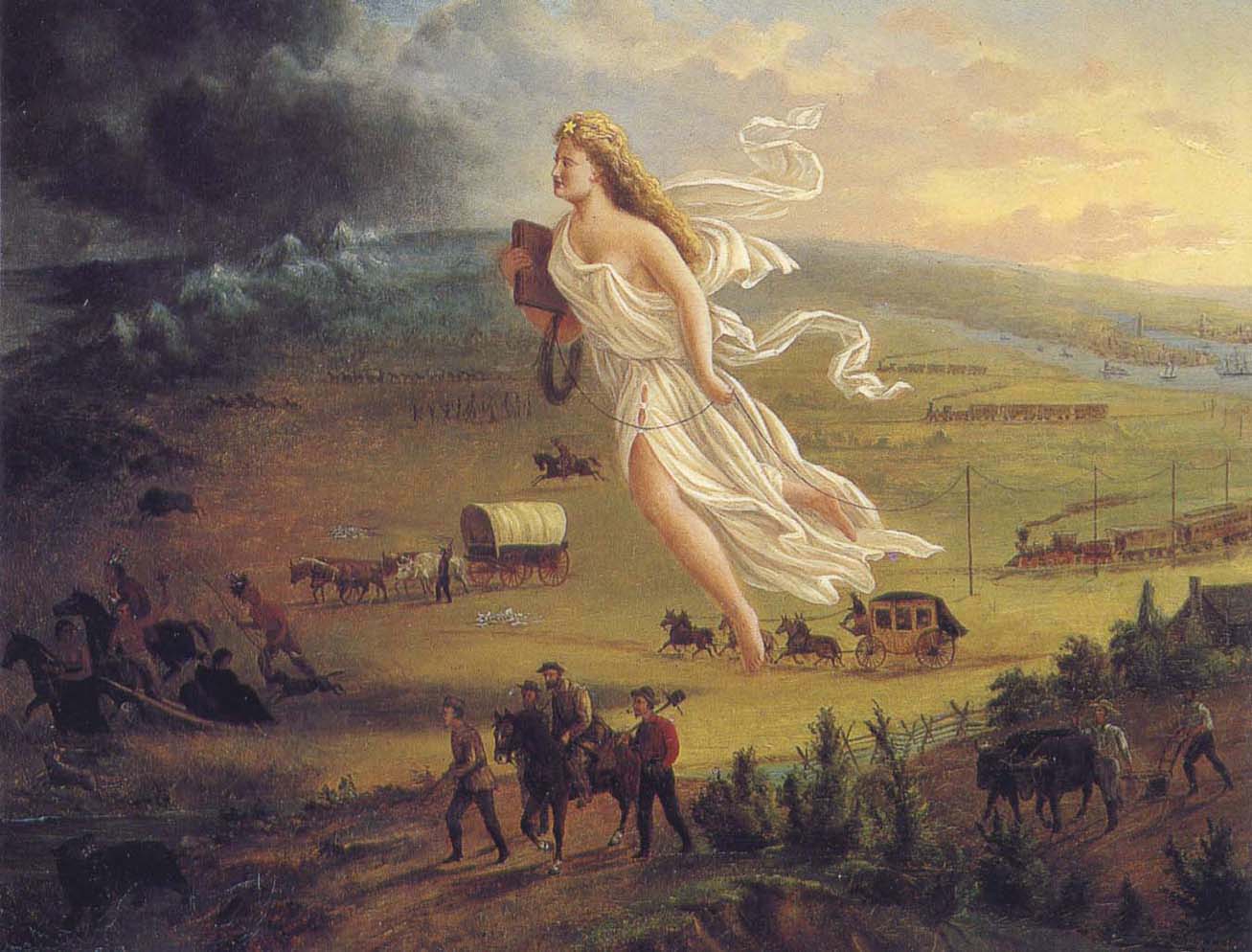

The emphasis on identity, she said, also reflects a subtle leftward tilt in the standards that did not exist before. Robbins pointed towards the new framework’s narrative on Manifest Destiny as a quintessential example of the new approach’s shortcomings. The portion of the framework dealing with Manifest Destiny reads, in full:

“The idea of Manifest Destiny, which asserted U.S. power in the Western Hemisphere and supported U.S. expansion westward, was based on a belief in white racial superiority and a sense of American cultural superiority, and helped to shape the era’s political debates.”

While this description isn’t false, Robbins said, the problem is one of omission. The College Board’s summary, she argues, reduces 19th-century Americans to “racists who thought they were better than other people,” while ignoring other more noble elements of Manifest Destiny, such as confidence in America’s republican system (as opposed to the monarchies of Europe) and the belief that this system should be an example to the world.

Robbins sees a similar issue in play with how the framework sums up Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy:

“President Ronald Reagan, who initially rejected detente with increased defense spending, military action, and bellicose rhetoric, later developed a friendly relationship with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, leading to significant arms reductions in both countries.”

“To any normal-thinking human being, that is a negative statement about Ronald Reagan,” said Robbins, who argues the wording paints Reagan as a foolish warmonger who “comes around” to the realization that a more conciliatory approach towards the Soviet Union was ideal.

How has so much alleged bias suddenly crept up in APUSH? The explanation lies in the much greater length and detail of the new framework’s topic outline. The old framework had a brief 5-page outline of topics that an APUSH class should cover, while granting substantial leeway to teachers to use state standards along with the backlog of earlier exams to fill in the gaps. For example, on the subject of the Great Depression, the old framework only required that the following topics be covered:

-Causes of the Great Depression

-The Hoover administration’s response

-Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal

-Labor and union recognition

-The New Deal coalition and its critics from the Right and the Left

-Surviving hard times: American society during the Great Depression

In contrast, the new topic outline is nearly ten times longer at 47 pages. Instead of simply saying a topic should be covered, the outline is replete with historical judgments. For example, one of three paragraphs on the New Deal sums it up by saying:

“Although the New Deal did not completely overcome the Depression, it left a legacy of reforms and agencies that endeavored to make society and individuals more secure, and it helped foster a long-term political realignment in which many ethnic groups, African-Americans, and working-class communities identified with the Democratic Party.”

Despite being substantially longer, the new framework actually de-emphasizes specific factual knowledge by listing handfuls of particular facts as the ones teachers have the “flexibility” to cover. For example, the section on the Civil War notes that teachers could use the Battle of Gettysburg or Sherman’s March to the Sea as key facts, while leaving out other critical flash points like the Battle of Antietam.

Teachers could, of course, still cover these, but the College Board has previous stated on its website that nothing would be asked on the test that wasn’t also in the framework. That line has since been removed, but Robbins says the College Board has given no indication its intent has changed.

The changes to the framework would matter little if they had no bearing on the test. However, a practice test for the new version released last year by the College Board indicates that the changes to the framework have translated into a huge shift in the style of the AP test itself. The changes are far from minor, and are readily visible to anybody who compares the practice test to past versions.

The big shift in the test is, in essence, a radically reduced reliance on test-takers to demonstrate factual knowledge of American history.

The 1996 exam, for instance, asks specific questions about the historical policies of more than ten different presidents, in the vein of “Andrew Jackson supported all of the following EXCEPT … ” Students who lacked a basic understanding of what policies notable presidents pursued could not expect to perform well on the test.

In contrast, it’s not immediately clear that the new AP exam would even require students to know the names of most presidents, let alone what their major policies were.

The new multiple-choice section focuses on answering questions about primary source documents, such as speeches or Supreme Court decisions. While a few presidents are quoted in the released practice test, answering the related questions typically requires only reading comprehension rather than any knowledge about the presidents themselves.

For example, one document to be analyzed is Reagan’s famous “Tear Down This Wall” speech in Berlin.

Students are asked what change in American foreign policy the speech represents, with the options including “caution resulting from earlier setbacks in international affairs,” “increased assertiveness and bellicosity,” “the expansion of peacekeeping efforts,” or “the pursuit of free trade worldwide.” Concluding that the second option is the best answer requires only reading the speech, not any actual historical knowledge of Reagan or his policies.

In the process of de-emphasizing facts, the College Board has also created more room for narrative building.

One portion of the test, for example, shows a famous photo by Jacob Riis of impoverished residents of 19th century New York. The picture is then used to ask three questions: What the photo helped contribute to (greater Progressive activity), why the people lived in such poor conditions (low wages), and what “advocates” for the poor individuals would have favored (more government regulation).

The College Board has defended this shift by arguing that it wants to avoid forcing students to memorize mountains of facts. Robbins says this is an excuse that conceals lower knowledge expectations.

“You can refer to it as rote memorization. It can also be referred to as ‘learning,’” she said. ”We think students should learn American history. It’s hard to think critically about a fact if you don’t know the fact.”

The College Board has launched a strong rebuttal of other accusations leveled against the new test, as well. The lack of focus on important people and organizations, they say, is intended to give states and individual teachers the freedom to use their own standards and judgment to decide what is covered. It has also pointed out that its earlier framework was similar to the current one in its lack of focus on individual people and facts.

Critics, however, see this as a ludicrous dodge. The central goal of any AP class is to prepare students to pass the end-of-year exam. Most teachers, they argue, will not spend time on material that won’t be covered on the test. Since the new test expects less specific knowledge of students, whether its on important figures or important documents, their knowledge will accordingly be measurably less. Nor should the new framework simply be compared to the old one, because the new one is so much more in-depth.

“The structure of the new test reduces the opportunity students will have to introduce outside content,” Robbins said. “They won’t get as many points for that as they did under the old test.”

The Board has also defended its new approach by pointing out that APUSH is supposed to simulate a college course, and that accordingly students should already have a basic factual grasp of U.S. History before taking the course.

In fact, Robbins says, that’s routinely not the case, because APUSH is simply treated as the de facto advanced history course in high school.

“For many kids, this is the only real US history course they’ll ever take,” she said. “Kids don’t take basic US history and then the AP version. They take APUSH instead of the alternative.”

Ultimately, Robbins says, the problem is one of an agenda, whether the College Board intends it or not.

“Are there some positive things [in the new test]? Sure. The negative just really outweighs the positive,” she said. ”The College Board has an agenda here. If they didn’t, this framework wouldn’t exist.”

The solution? Return to the old, less biased framework … or take action to deprive the College Board of its influence.

“It’s not acceptable for them to have this kind of monopoly,” said Robbins. If parents and legislators think the new APUSH test is too biased, they should work to create an alternative test, she said, and the sooner, the better.

Content created by The Daily Caller News Foundation is available without charge to any eligible news publisher that can provide a large audience. For licensing opportunities of our original content, please contact licensing@