by Ian Huyett

It’s sometimes suggested that libertarian ideas are hazardous because they lack precedent. Functioning decentralized societies, it’s implied, are absent from humanity’s past.

Yet throughout recorded history, nations have survived and thrived without the overarching authority that President Obama assures us is necessary for prosperity.

My observation is nothing new. Each of the systems I’ll name here has been the subject of at least one lengthy examination by a libertarian scholar. I have yet to come across, however, a reference sheet that briefly reviews a few of them. I’ll attempt to provide one below.

Icelandic Godord

It’s not a coincidence that many advocates of liberty see a paradise amidst the pages of Iceland’s sagas. To hear some medieval historians tell it, Iceland was founded as something of a 9th century Free State Project. “According… to their own histories” says Carolyne Larrington of St John’s College, Oxford “the Norwegians migrated from Norway because King Harold Fairhair was centralizing power there.”

The creation of Iceland was, first and foremost, a flight from overarching government. Iceland was founded to protect traditional Norwegian values: an emphasis on community, a respect for competition and a commitment to individual responsibility.

Because Icelanders rejected kingship, men who wished to become godar – religious and political leaders – had to persuade others to follow them voluntarily. Iceland – which is about the size of Virginia – was consequently divided into dozens of small chieftaincies, or godord.

These chieftains had no royal claim to the lives of their constituents, who were free to leave and join other godord at any time. This made leaders accountable to their followers and created a market for fairness and efficiency in government.

Each chieftaincy collected voluntary taxes in the form of temple dues. In turn, they provided judges and lawyers whose job it was – failing a mediation in private court – to arbitrate between or advocate for their subjects as needed.

While power in Iceland was eventually centralized, the godord system stood for nearly three centuries. As Roderick Long has pointed out, “We should be cautious in labeling as a failure a political experiment that flourished longer than the United States has even existed.”

Xeer

The system differs from Iceland’s in that membership in one’s clan – or qabil – is fixed at birth. It affords even greater competition, however, between private courts, or guurti. These courts – which traditionally meet beneath Acacia trees – are financed by donations from local businessmen. For the businessmen, these donations serve as a kind of advertisement.

Xeer is nearly identical to its Icelandic equivalent in its focus on restitution and its practice of exiling repeat offenders. Somalia’s legal lexicon, however, contains virtually no loan words. As I see it, then, godor, xeer and similar systems that have independently emerged elsewhere suggest an intuitive human legal order.

Somalia’s present, unfortunate state stems from a transgression of that order: the reign of Marxist tyrant Siad Barre, who violently suppressed the xeer tradition in the name of egalitarianism. Barre not only outlawed the customary question “what is your clan?”, but banned the question “what is your ex-clan?” soon after.

As George Mason’s Peter Leeson has shown in great detail, most measures of well-being in Somalia have actually improved since the implosion of Barre’s centralized state. Yet Somalia’s libertarian folkways are under constant attack by the nation’s Westernized intelligentsia, who abhor “qabilists” as backwards reactionaries that refuse to embrace the modern era.

Carolingian Law

Charlemagne was an overwhelmingly successful conqueror: the King of the Franks more than doubled the territory he inherited from his father and is credited with an intellectual revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance. Ironically, medieval historians say that a policy of legal decentralism made the Emperor’s successes possible.

Though Charlemagne waged a campaign of terrorism against Saxony, he had a remarkable respect for the sovereignty of communities within his borders. Internally, the Holy Roman Empire was a loose confederation of small principalities that were encouraged to retain contradictory sets of laws. Consider the words of University of London historian Tom Asbridge:

“Today, we’re thinking about how is Europe going to live together – the European Union – and we’re trying out different models. We’re trying out a model of centralized power, in which we all follow sort of a similar set of laws, a similar set of practices. And the alternative, of course, is to have a loose conglomeration of powers, and we all follow slightly different forms of law, but we get on, we cooperate. The interesting thing is that Charlemagne’s vision of his empire – of the equivalent of Europe – was to allow people to follow quite different sets of laws depending on their local region, their traditions. And to have a loose umbrella of power that held it all together. That actually worked for Charlemagne. Later generations, his successors – Louie in particular – tried to enforce centralized power, and that didn’t work. So perhaps there’s a lesson for us to learn about Europe: Charlemagne’s way of diversity in unity perhaps is the way forward.”

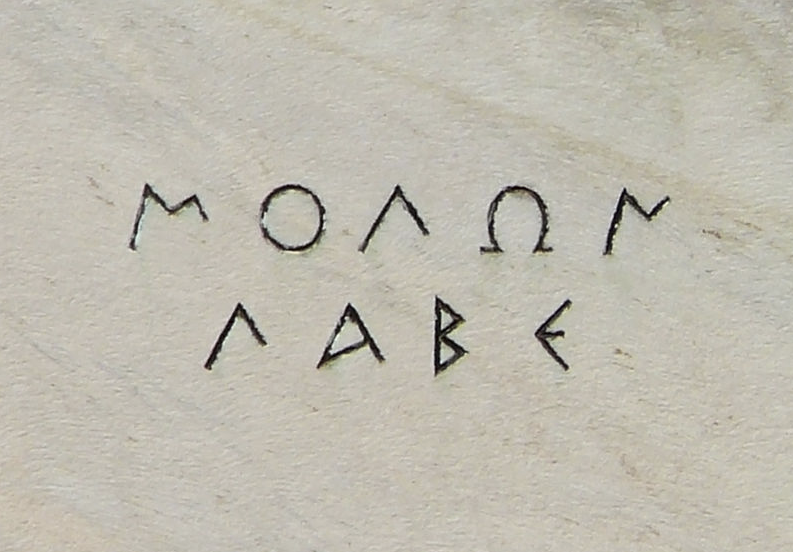

The Hoplite-Farmer

“Cypselus, like just about all the tyrants, used his power to do something that the Greek governments normally did not do: namely, collect taxes from their people.

You have to understand that the idea of taxation being normal would have gotten a Greek foaming at the mouth. When there’s no tyranny, there’s no taxation…

The normal form of taxation that existed in the Greek world – when it was in its independent polis phase – was simply customs duties on trade. But the hoplite-farmer wasn’t gonna be taxed. Paying taxes is what barbarians did to their kings. A very powerful feeling.”

Cypselus’ imposition of taxes on Corinth doubtless appeared horrible because it could be contrasted with the many other independent polities that made up Greek civilization. Our species has formed communities since we could walk on two legs. Those communities, when allowed to emerge and compete, are under pressure to afford us freedom.

While cumbersome superstates seem like today’s default arrangement, they are ultimately a blip on the timeline of human existence. Libertarianism offers a legal arrangement that, far from being counterintuitive, is grounded in long established common sense.