“I am like any other man. All I do is supply a demand.” – Al Capone

The temperance movement – the collective effort of some to decrease and even eliminate the consumption of alcohol – gained a foothold in the United States in the 19th century and their efforts culminated in the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 1919; the amendment that ushered in the prohibition of alcohol.

In theory, prohibition was supposed to lessen access to alcohol and therefore lessen its use. Initially the theory seemed to work in practice as overall alcohol consumption did go down. But then alcohol use entered a phase of stead increase as the black market that grew up around prohibition increased the supply of illegal booze to the masses.

But alcohol prohibition had another effect, one that was much more dangerous to society as a whole than alcohol itself could ever be. The prohibition of alcohol was almost immediately accompanied by a drastic increase in crime, across the board. Murder, robbery, assault; all serious crimes saw increases.

From The Cato Institute:

“America had experienced a gradual decline in the rate of serious crimes over much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. That trend was unintentionally reversed by the efforts of the Prohibition movement. The homicide rate in large cities increased from 5.6 per 100,000 population during the first decade of the century to 8.4 during the second decade when the Harrison Narcotics Act, a wave of state alcohol prohibitions, and World War I alcohol restrictions were enacted. The homicide rate increased to 10 per 100,000 population during the 1920s, a 78 percent increase over the pre-Prohibition period.

“The Volstead Act, passed to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment, had an immediate impact on crime. According to a study of 30 major U.S. cities, the number of crimes increased 24 percent between 1920 and 1921. The study revealed that during that period more money was spent on police (11.4+ percent) and more people were arrested for violating Prohibition laws (102+ percent). But increased law enforcement efforts did not appear to reduce drinking: arrests for drunkenness and disorderly conduct increased 41 percent, and arrests of drunken drivers increased 81 percent. Among crimes with victims, thefts and burglaries increased 9 percent, while homicides and incidents of assault and battery increased 13 percent.”

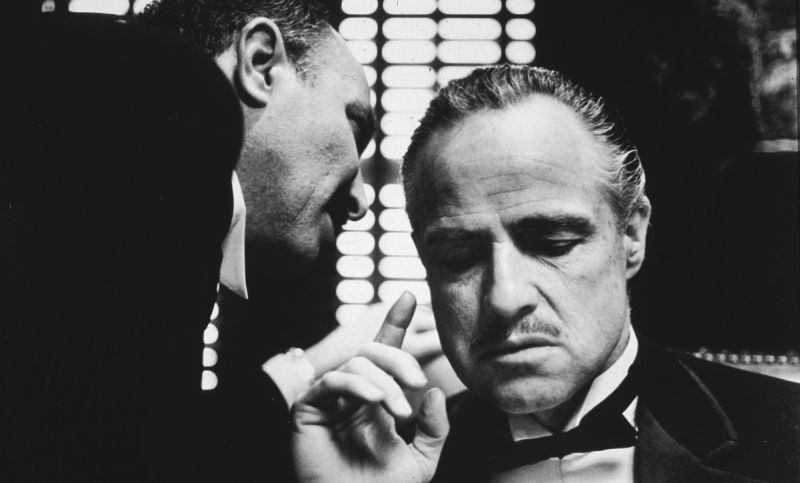

Not only was crime more prevalent, the profits to be made from illegal alcohol caused it to become more organized. Many are familiar with the illegal empires built by the likes of Al Capone in Chicago and Joe Masseria, Salvatore Maranzano, and later Charles “Lucky” Luciano in New York City. The profits made from these years allowed the American Mafia to continue to grow in power and wealth long after prohibition was repealed.

A lot of crime that occurred during alcohol prohibition can be traced back to the disastrous economic effects. From the Ken Burns documentary Prohibition:

“Prohibition’s supporters were initially surprised by what did not come to pass during the dry era. When the law went into effect, they expected sales of clothing and household goods to skyrocket. Real estate developers and landlords expected rents to rise as saloons closed and neighborhoods improved. Chewing gum, grape juice, and soft drink companies all expected growth. Theater producers expected new crowds as Americans looked for new ways to entertain themselves without alcohol. None of it came to pass.

“Instead, the unintended consequences proved to be a decline in amusement and entertainment industries across the board. Restaurants failed, as they could no longer make a profit without legal liquor sales. Theater revenues declined rather than increase, and few of the other economic benefits that had been predicted came to pass.

“On the whole, the initial economic effects of Prohibition were largely negative. The closing of breweries, distilleries and saloons led to the elimination of thousands of jobs, and in turn thousands more jobs were eliminated for barrel makers, truckers, waiters, and other related trades.”

The years of alcohol prohibition were also more deadly for police. From 1918 to 1921 alone there was a 46% increase in the number of police officers killed. Put another way, there were 166 officer deaths in 1918; in 1921 that number went over 200, staying there every year until 1936, peaking at 304 deaths in 1930. Prohibition was repealed in 1933 and officer deaths began to decline, dipping below 200 in 1936 and below 100 by 1943. In fact, the number of officer deaths in a year wouldn’t reach 200 again until the year 1970, which is a pivotal year in part 2 of this series concerning the war on drugs.

It is not enough to say alcohol prohibition was a failure. That implies that the results desired weren’t quite reached and that’s the extent of the problem. But alcohol prohibition went way beyond failure; it was an actively destructive force that made many areas of society much worse off than they had been under the status quo. It lead to more crime, more corruption, less prosperity, and more death while laying the foundation for the largest criminal organizations ever created in the United States.

We learned many lessons from the prohibition of alcohol; unfortunately these lessons weren’t enough to prevent similar actions being taken to try and curtail the sale and use of illicit drugs, a subject we will tackle in the next part of this series, coming soon!